The unclarity regarding the incident on the Egyptian border, in which three Israeli soldiers were killed, is beginning to dispel as the results of the investigation of the affair are published. Contrary to opinions voiced until the publication, speculating mainly on the performance of the soldiers themselves – the inquiry focuses on other aspects of the attack, and justly so. From my experience in the field, both as brigade commander, in charge of that very same sector for two years, and as Deputy Inspector General of Israel’s Defense Establishment, I know that when outcomes in the field are harsh, what is needed first and foremost is a thorough examination of the failures in planning and the surrounding dimensions, which, if left untreated, we will not be able to learn the required lessons and make the needed improvements. This is precisely the point that the investigation puts forth.

Before we delve into the thick of things, it is important to stress that without an understanding of the background and circumstances of the force’s activities along the border with Egypt – it would be difficult to comprehend the incident and the failures leading to it.

The Horseshoe Route: A Difficult and Complex Border

Israel’s border with Egypt may seem to many Israelis as a quiet and peaceful border with a country with whom Israel has a peace agreement. But nothing could be further than the truth in reality. In order to understand why, we need to go back some 100 years in history.

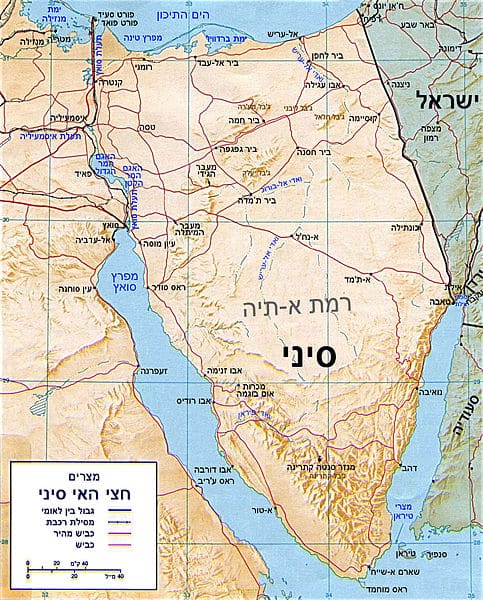

In 1906, the Ottomans and British charted the border between Egypt and the Land of Israel, carving each a territory according to their preference – while the Ottomans opted for a high topographical advantage, the British preferred control over sources of water. Thus the Ottomans retained the Negev Mountains while the British seized nearly all water sources along the border on its Sinai side.

The result was a contrived border, and as such, had little to no effect on the local Bedouin tribes, as the tribes, who now found themselves arbitrarily divided on two sides of a border, had indisputable familial and tribal relationships: every Bedouin tribe on the Israeli side of the border has a kin tribe on the Egyptian side – like the Azazma or Tarabin tribes, for example.

Throughout most of its existence, Israel had no fence along its border with Egypt and the border was left for the most part unsupervised. This allowed for the profuse smuggling of drugs and arms and human trafficking activity, in part designated for Israel and in some cases – traversing Israel en route to and from the Fertile Crescent region. The result was a long porous border that was a haven for a vast smuggling enterprise, which took on various forms throughout the years.

Two additional elements later came into play, altering the border’s character as a potential gateway for terrorism against Israel: one was the Islamization of the Sinai Bedouins, and the other was Israel’s disengagement from the Gaza Strip, which ultimately resulted in the fostering of ties between Gaza’s terrorist groups in and Egyptian territory.

Both developments gradually changed the nature of the smuggling activity – once purely commercial – into a terrorism-bound endeavor, thus the “horseshoe route” came to be: a supply route for terrorism, stretching from the Gaza Strip, cutting through the Sinai Peninsula, and turning back to reach Israel through the Israel-Egypt border. Since the 2005 Israeli Disengagement from Gaza, this highly maintained route has been operated by Bedouin tribes – starting from Egypt, in the Rafah area, where Bedouins liaise with a suicide terrorist from Hamas or other organizations, take him a short distance through the Sinai Peninsula and back to the border with Israel to leave him in the charge of Israeli Bedouins, who take him into Israel’s territory to commit attacks against Israeli civilian and military targets.

Some of these infiltrations of terrorist elements hit hard in the heart of Israel. Such was the case in January 2007, in which a terrorist came into Israel from Gaza through the aforementioned horseshoe route, arrived in the Southern town of Eilat and detonated his explosive vest in a bakery in the city, killing three Israeli citizens; or the attack near Eilat on Route 12, in August 18 2011, only this time, the attack was executed by ISIS terrorist squads, calling the Defense System’s attention to a new kind of threat.

The Border Fence: From “Wholesale” Smuggling to “Ladder” Drop-offs

Yet, it was not the prolific smuggling activity, nor was it the mounting terrorism from Gaza – and later, on part of ISIS – that propelled Israel to put up a border fence and establish an intel gathering array on the Egyptian border. The catalyst was in fact the influx of labor seekers from Sudan and Eritrea into Israel, a mass hegira that was perceived as a potential threat to the Jewish nature of the State of Israel. It became evident that unless the border was sealed, Israel would radically change, and the takeover of Tel Aviv’s southern neighborhood by this population – which has become a breeding ground for harsh crime and violence – might plague cities across the country.

Hence the state of affairs on the Israel-Egypt border underwent marked change in 2013, upon the installation of the border fence. Aimed predominantly at thwarting infiltrations, it also had a positive effect on thwarting smuggling activity, which saw a decline. Whereas prior to the installment of the border fence, smuggling was done on a large scale, using among others camel convoys carrying contraband such as arms across the border, once the fence was in place, a new method of smuggling was adopted: “fence drop-offs”, whereby a smuggler on the Egyptian side of the border would climb a ladder and drop the contraband over the fence, to be collected by a counterpart on the Israeli side of the border, who quickly vanishes into Israeli territory with the goods.

The changing reality along the border had a de facto effect on the IDF’s deployment in the area. Now charged with the protection of 220 kilometers (137 miles) of border by means of routine security activity along the fence, where infiltration or smuggling attempts are almost a nightly affair. This is performed with a limited military force.

The IDF array that was established for the purpose of border security, included the border fence itself, alongside a network of watch-towers and guard posts, which were devised to support and cover each other when necessary. As mentioned, the border fence was built with a single purpose in mind which is to prevent infiltrators from breaching the border. For this reason, the fence was planned with no openings whatsoever. Later, emerging security demands required movement of troops across certain areas of the fence and the military installed clandestine passages. It was through one of these passages that the Egyptian terrorist infiltrated Israel.

The manner in which the border security array was planned, means that the soldiers are demanded to man the posts along the fence under harsh and grueling conditions, not the least of which are demanding physical conditions such as extreme heat and cold and strong winds, while upkeeping an intensive activity regime. In my time as the sector’s Brigade Commander, I worked closely with these battalions, and was involved in the development of their training program, alongside Major General Galant – now the Israeli Defense Minister, and I can personally attest that they do their job to the highest standard, with composure and to precision, such that successfully intercepts smuggling attempts and even terrorist attacks.

This array, set up by the IDF after installing the border fence, was put to the test in the recent incident, which exposed crucial planning shortcomings, which must be examined.

Systemic Failure? A Series of Shortcomings with A Tragic Ending

The key factors arising from the army’s investigation of the incident, allegedly point to a series of shortcomings and failures that led to the tragic conclusion of the event.

The first failure was the lack of preliminary intelligence regarding the Egyptian policeman’s plans to carry out an attack on Israeli soil. The second failure was the gate with which the terrorist was very much familiar and through which he entered Israel – it was not locked as protocol demands, rather tied shut with a plastic zip tie which the terrorist had no problem cutting. The third shortcoming was the failure of the watchtower guards to identify the terrorist’s infiltration into Israel’s territory, among others due to the fact that they were not specifically instructed to scan the clandestine passages. In that sense, the passage through which the terrorist crossed the border was hidden from our forces but not from the terrorist.

The fourth failure, and in my opinion the most blatant of them all, is the succession of events even before the terrorist crossed the fence: the deployment of troops and work load allotment – posting only two soldiers in an isolated guard post for a 12-hour shift, without maintaining communications with them on an hourly basis, is a sure formula for disaster. The claim that the post is not secluded and that there is a network of posts that cover one another – proved fallible, since once the terrorist opened fire at the soldiers, none of the other posts heard the shots or noticed what was happening.

It is possible that the mission description focused on the prevention of smuggling detracted from the equally important imperative to protect the border from terrorist attacks. Thus, despite the formal procedure that calls for a minimum of a 4-person team for any operational mission, only two soldiers were posted at the guard-posts along the border. For this reason, as the sector’s Brigade Commander, I’ve never sent less them four soldiers at a time for such missions.

The need to spread the personnel for each mission to the extent possible is understandable, however, in this case the mission objective was not fully specified to address the threat of terrorism, and consequently, risks were not properly managed, to a detrimental result.

Risk management planning should also have been evident as the incident itself unfolded – when the soldiers’ bodies were discovered in the guard post and the terrorist was spotted by the surveillance operators: Israeli forces closed in on the terrorist, and during the exchange of fire, yet another soldier was killed. Of course engaging a hostile is necessary – a value upheld in the IDF. However, as the terrain in the site of the attack is wild, with no populated areas in the near vicinity, the proper course of action was to wait for backup. Engaging a hostile is not an end – but a means to an end.

It is important to understand that in routine security activity, the devil is in the details. Thus, for example, the deployment of forces should have been such that the guard posts could cover each other – not just on the planning charts, but in practice. The forces in the field should have been well informed about the clandestine border passages, and surveillance teams should have been specifically instructed to observe those areas as well, at least those not in the posts’ blind spots. Furthermore, the gate should have been properly locked rather than secured with a zip tie.

Public Lesson: Don’t Blame the Guard at the Gate

Thus far, I’ve addressed the systemic and planning failures that led to the dismal outcomes of the incident, I would like to mention another shortcoming, on our – the public’s – part, and just as much – on the part of the media. As often happens in such grave events, until the picture becomes clear, some voices pounce to analyze the soldiers’ performance during the event – what they did; what they didn’t do; does their mixed female and male unit have the ability to uphold a proper operational condition or not, and so on and so forth.

I say this with the utmost clarity: as a Brigade Commander of the sector’s Caracal Battalion, which performs exceptionally – such as the female fighters from the battalion, who engaged with hostiles and intercepted numerous potentially dangerous incidents almost on a weekly basis – the soldiers protecting Israel are nothing short of heroes. Perhaps there were shortcomings in the level of their performance. We will never know. But there is no doubt that the conditions created for them to begin with were not up to par with what should be expected and should have been in place to allow them to accomplish the mission with which they were charged. Blaming the guard at the gate never got anyone anywhere. The rectifying of systemic and command failures demands first and foremost an examination of the system itself, and it seems that at present, the military command is aiming exactly for that. Thankfully.