Authors: Adv. Yifa Segal, Lt. Col. (Res.) Baruch Yedid, Jennifer Teale

Editing and guidance: Or Yissachar

Professional consultancy: Brig. Gen. (Res.) Yossi Kuperwasser

Graphic design: Natanel Kenan Studio | Nat.co.il

About the IDSF

IDSF – Israel’s Defense and Security Forum, Habithonistim is a movement with more than 35,000 senior officers, commanders and combatants in the reserves and civilians who are former members of all the security forces. It was founded in order to defend the state of Israel’s security needs in a way that will enable it to exist and prosper for generations to come.

Our policy is clear: We are committed to Israel’s right to safe borders, the borders of the land of Israel; we believe that Israel’s security needs head the national priorities; and we believe that Israel does not have the privilege of losing any war. The IDF must act freely in the entire area in order to fulfill its responsibility and to defend Israel.

We clarify that the movement is non-partisan, but puts the values and the vision that define it at the forefront.

Our management

Chairman and Founder: Brigadier General (res.) Amir Avivi

CEO: Lieutenant Colonel (res.) Yaron Buskila

Or Yissachar, Assaf Voll, Jessica Barazani, Ortal Ron, Moshe Davis, Elie Pieprz, Keren Balila, Ronit Farkash, Eva Nagar, Lt Col (res) Tal Nir, Yitshak Lev, Ariel Shafir

Our board of directors

Major General (res.) Gershon Hacohen, Major General (res.) Yitzhak Gerry Gershon, Commissioner (res.) Shlomo Katabi

Among our members

Major General (res.) Yossi Bachar, Major General (res.) Kamil Abu Rukun, Major General (res.) Yossi Mishlav, A., a former senior officer in the Mossad, M., a former senior officer in the General Security Services, former Commissioner Shlomo Katabi, Brigadier General (res.) Hasson Hasson, Brigadier General (res.) Harel Knafo, Brigadier General (res.) Avigdor Kahalani, Brigadier General (res.) Yossi Kuperwasser, Colonel (res.) Tal Braun, Prof. Alexander Bleigh

Program principles

Israeli Humanitarian Directorate

Israel will oversee the aid distributed by international organizations, effectively dismantling the distribution networks of UNRWA and Hamas in the Gaza Strip, guided by the principle: “The hand that distributes the aid is the hand that controls it.”

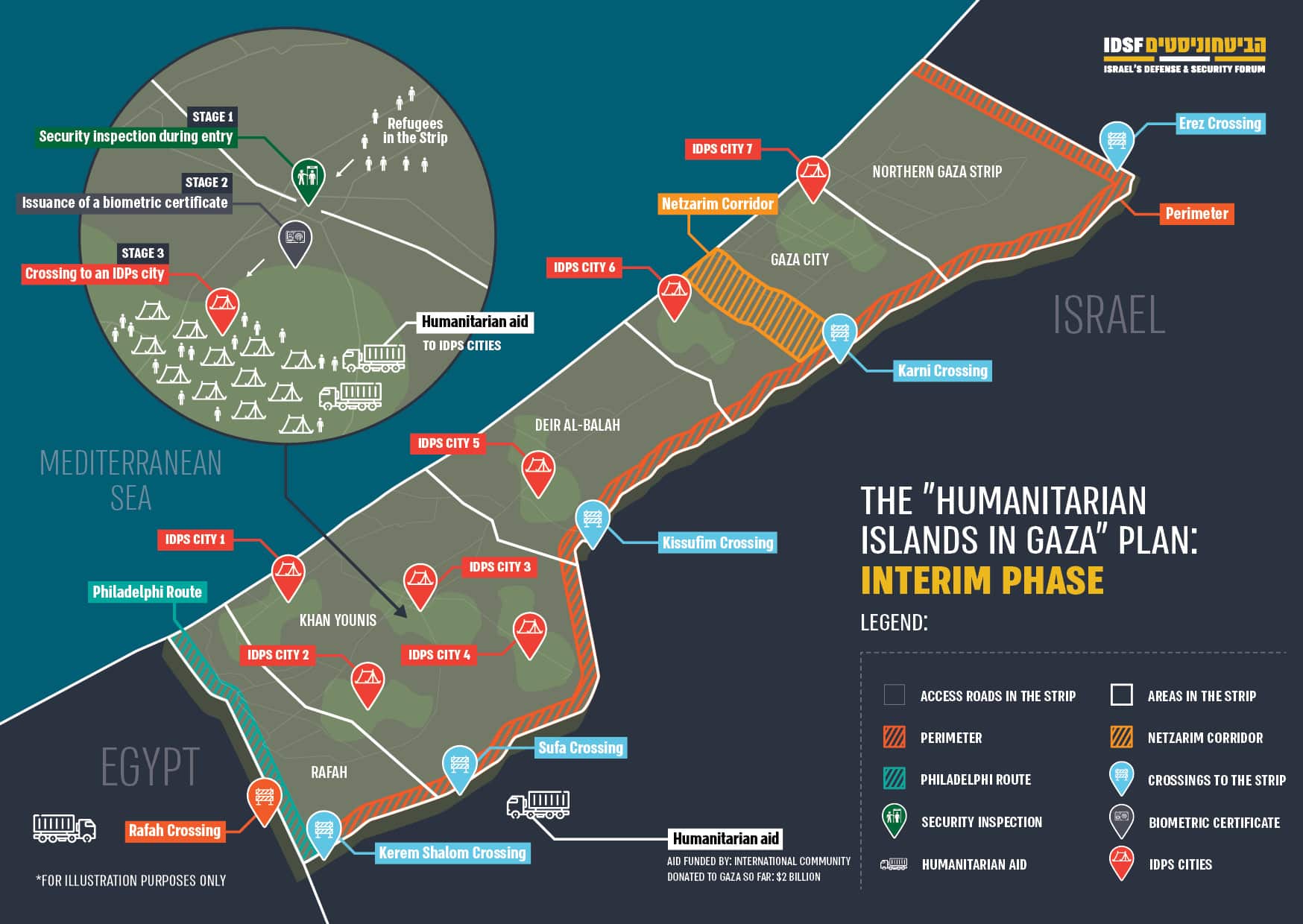

IDP cities

Humanitarian zones will be established in open areas based on international disaster response models and aligned with the UNHCR’s Needs Assessment for Refugee Emergencies (NARE) guidelines.

Gaza’s division and zoning

According to the “divide and rule” principle, a system of longitudinal and transverse axes will partition the Gaza Strip into distinct segments, restricting population movement between them.

Humanitarian, rather than political role

The humanitarian islands will not serve as a political solution but will provide an interim step toward a final settlement in Gaza.

International aid

Aid will be delivered directly to the population through international donations, not the Israeli taxpayer. |Actionable: Since October 7, 2023, donations totaling $2 billion have funded the delivery of over 1 million tons of aid transported in 60,000 trucks.

Introduction

After suffering the October 7 massacre, Israel embarked on the Swords of Iron war in the Gaza Strip, along with additional theaters of war. Following the ground maneuver, the IDF issued instructions for Gaza’s civilian population to evacuate the battle areas in order to minimize harm to non-combatants and allow for orderly operational deployment. Concurrently with a wide-ranging humanitarian operation which to date has achieved distribution of roughly a million tons of humanitarian aid in the Gaza Strip, the humanitarian situation there has remained a challenge as Hamas continues to steal considerable quantities of the aid. Meanwhile, extensive built-up areas have been left destroyed, or are no longer inhabitable, in the wake of the IDF’s operational deployment against the extensive terrorist infrastructures from which Hamas was operating. More than a million Gazans have been designated IDPs (internally displaced people) after evacuation from their homes.

Over and above the situation on the ground and the needs that it generates, security and strategic needs arise as well. The existing Hamas infrastructures, through which Hamas controls the population and maintains its power, are largely based on pre-existing infrastructures above ground and underground — as well as on the Gazan social structure, by means of which Hamas has solidified its hold and its dominance over the years.

For those reasons, it is currently neither feasible nor recommended that the IDPs return at the conclusion of the war.

A system should be adopted that can on the one hand optimally assist the population as circumstances require while on the other hand not returning power and control to Hamas.

More than a year into the Swords of Iron war in the Gazan theater, fighting still continues significantly despite the end of the major intensive phase. In the meantime, Israel has not yet officially entered the next phase — the interim phase between fighting and a long-term arrangement in Gaza.

At present, it is already clear that the end of intensive fighting does not mean the end of fighting, and apparently the phase of “mopping up”, or “clearing” — the battle in pockets of Hamas activity — will last a long while.

Alongside the question of fighting is the question of The Day After: Who will assume administration of the Gaza Strip, when, and how? It is not yet clear what official plan will eventually be adopted by the Israeli government. (We once more recommend the December 2023 Gaza Security and Recovery Program published jointly with JCFA and presented to top Israeli decision-makers.) However, it is definitely clear that none of the proposed programs can be started immediately. Therefore there must be an interim phase, which our program calls the “mechanism construction phase.” That period will last for at least several months and might even require a year or two.

The proposed model for the interim phase involves the construction of a temporary Humanitarian Directorate in the Gaza Strip, purely civilian in character and with no political attributes. The model’s implementation will involve the construction, on vacant spaces, of IDP cities. As it relates to the construction of IDP cities, commonly-used models around the world can be of hand, with extensive international experience in their implementation – whether in response to natural disasters or to the ravages of war.

In light of the plentiful and successful international experience, this model can be quickly and efficiently applied. Moreover, it can be applied immediately and gradually so that there will be no need even to wait for the official end of the war or the end of the current phase of fighting. Implementation can and should be gradual. The first IDPs would be constructed in the northern Gaza Strip where the military and administrative hold of Hamas is relatively slight. With the success of the model and in consideration of the needs and opportunities in the field, the system can be extended to other parts of the Gaza Strip.

As noted above, this paper deals with the interim phase and posits the establishment of a Humanitarian Directorate with purposes confined to answering basic immediate, critical needs of the Gaza Strip’s residents. The Humanitarian Directorate will not seek to solve complicated political problems or to suggest long-term solutions. Rather, it will facilitate an efficient flow of humanitarian aid to the Gaza Strip’s residents, while denying Hamas control over the population and over the aid resources that have enabled Hamas to survive.

The program will seek to demonstrate how those two objectives can be simultaneously met, and it is compatible with the war objectives Israel has set. This is in contradiction to the claim that in order to prevent a humanitarian disaster in Gaza, the existing mechanisms such as UNRWA must be preserved or, worse yet, the civil authority of Hamas must be accepted.

Later, this paper will consider suggestions for returning the system of a “military administration” to Gaza. While this system offers certain undoubted advantages, particularly because the IDF gained much experience in operating it efficiently over the pre-Oslo years, it also carries many disadvantages. This paper proposes new models, from sources including case studies in management of humanitarian crisis areas around the world. The models incorporate out-of-the-box thinking, understanding of the failures among past models, and aspects of successful models from other parts of the world.

At the same time, a distinction must be stressed: As this model is implemented, the attitude of the Palestinians, unlike that of the victims of natural disaster, is not to be taken for granted. Support for Hamas still runs high, and the local Hamas leadership may be expected to forcibly resist any project of this sort.

The Humanitarian Directorate will facilitate the achievement of the most important objectives in the interim phase while generating the minimum of resistance. First and foremost, it will facilitate preparations on the ground for the Day After, in the most efficient and unobtrusive way — relatively unobtrusive, specifically, at the international level. Second, it will facilitate prevention of a humanitarian crisis in Gaza and manage the aid resources efficiently, accelerate the process of eliminating Hamas as a governmental force, and ultimately build the foundation for granting a certain measure of managerial authority over civil matters to those in the Gazan population who are not involved in terrorism.

The Humanitarian Islands Plan for Gaza

Key points of the proposal

- Responsibility for humanitarian aid in Gaza will pass from UNRWA and Hamas to a Humanitarian Directorate based on IDP cities and biometric certificates.

- In general, the Humanitarian Directorate coordinating the operations will be Israeli, but the IDP cities and the aid in the field will be managed autonomously from inside the IDP cities by the local population and the aid organizations, according to the customary standards of international aid agencies, with no Israeli intervention in day-to-day administration. Aid missions will continue to be posted and funded as they are today, relying on the budgets of the various aid providers and not on an Israeli budget.

- Israel will be responsible for facilitating the system’s smooth, efficient operation. It will guard the perimeter of Israeli territory and of the crossings in the Gaza Strip outside the territory of the IDP cities.

- Financial responsibility will not rest with the Israeli taxpayer, but rather with international donors as is the case in Gaza today and in many of the world’s disaster areas.

- Civil and apolitical: The Humanitarian Directorate will have no political or diplomatic authority. Its role will be confined to the humanitarian plane.

- Proximity to the population, and control over aid, will also serve the objective of finding a realistic alternative to Hamas for the next phase of the Day After in Gaza.

- For security purposes, the IDF will retain complete freedom of operation throughout the Gaza Strip, including the humanitarian islands, under any scenario.

The difference from the current situation:

- “The allocating hand is the ruling hand”: The IDF will closely supervise the allocation of humanitarian aid, and it will deny UNRWA and Hamas control over the basic needs of the population, thus strengthening its ability to disempower Hamas and to oust UNRWA from Gaza.

- Proposing a horizon for the next phase of the war.

- Close supervision of aid in order to prevent Hamas or other gangs from taking control of the aid.

- Residents will enter with biometric certificates and undergo security checks and metal detection. Smuggling of weapons, and infiltration of Hamas or other hostile elements into the islands, will be prevented.

The model’s basic principles:

- Setting up IDP cities in pre-defined areas, according to an accepted international model for disaster zones

Description: IDP cities with temporary housing in open sites, outside the existing urban areas where damage is heavy or where the Hamas system of civil control still exists, or where terrorist infrastructures have remained above ground or underground. Humanitarian aid will be distributed only within the system of IDP cities and by means of the mechanisms to be established inside them.

Construction: The cities will be constructed by the aid organizations, after the IDF has cleared and allocated areas. Israel will assist as needed.

The principle of open areas: The cities are to be set up in open areas only, and only after the IDF has checked and ensured that there are no openings of terrorist tunnels in the intended area. Keeping Hamas out of the IDP cities is a top priority. Any access for Hamas operatives through terrorist tunnels could mean significant harm to the objectives for which the Humanitarian Directorate and IDP cities are intended. There should be readiness for a scenario in which Hamas tries to militarily disrupt the orderly routine at the IDP cities.

Examples of proposed models that may be implemented immediately

It is recommended to proceed according to the familiar models. UNHCR, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, has published detailed recommendations for the size of the recommended camp, the size of each room or tent, and the recommended services such as health, education, food, water, sanitation, administration, safety, logistics, etc. for the period of residence set by the agency.

The guidelines are titled NARE – Needs Assessment for Refugee Emergencies and are intended to enable agencies to evaluate the local population’s requirements and, on that basis, to determine the appropriate aid operations. The agency stresses that this list is dynamic and individually adjusted rather than compulsory clause by clause in every case.

The agency evaluates a long list of criteria according to categories, including conditions of geography and climate, the age distribution of the population, the health situation, unescorted children, women living alone, the nature of existing services (health, policing, sanitation, government offices), the factors that endangered the population, the resources existing at the location, the available sites for setting up new infrastructures, etc. Among the criteria used is the basic WASH criterion — Water (safe for drinking), Sanitation, Hygiene.

For a summary of the agency’s NARE procedures, use the following link:

And below is a link to the agency’s complete guide to the NARE procedures for assessing a population’s needs:

See the test case appendixes covering Iraq and Afghanistan for successful implementations of the procedures.

Experience from existing IDP cities in the Gaza Strip: Note that already today IDP cities of a sort are being set up throughout the Gaza Strip, but they differ significantly from the model proposed here. Firstly, the proposed IDP cities will be well ordered and well planned; they will not need to be set up without forethought. Second, the cities will be free of Hamas control and therefore more likely to succeed. Subsequently the population is less likely to undergo continual relocation, chiefly because Hamas will be unable to exploit the humanitarian systems as it currently does and mount terrorist activity from those areas.

- Establishment of the Humanitarian Directorate to serve as an administration responsible to the State Security Cabinet rather than to the IDF

Description: Transferring the responsibility for humanitarian aid distribution to the Gaza Humanitarian Directorate. Among the Directorate will be representatives of the IDF (including COGAT) and of the other security services, the government, and the international aid organizations.

Hierarchy: Each IDP city will interface with Israel’s General Humanitarian Coordination Authority.The General Humanitarian Coordination Authority will fill very limited roles, which will not include administration of the IDP cities’ internal affairs. Its roles will include:

- Coordinating the arrival of supplies

- Coordinating perimeter security

- Coordinating lists of residents and filtering Hamas operatives from them

- Coordinating the construction of new cities, defining the special areas for them, preparing them, and clearing them of underground infrastructures and other terrorist infrastructures

Management of the population: Each IDP city will be considered a separate temporary administrative territory, and its residents will receive biometric certificates unique to each IDP city, which will permit them to enter and receive humanitarian aid that is provided at the camp. Note that these are not identity cards; the residents are to use them to receive services, but not as a permanent solution. They will enable the population to be monitored as it passes through the crossings and will prevent operatives of Hamas and other terrorist organizations from entering.

In parallel, the operations of UNRWA in Gaza will be eliminated. Refugee certificates from UNRWA and identity cards from Hamas will be invalidated.

Local representation: In each IDP city, a local representative body will also be selected as is customary in the international model for IDP cities. The representative body’s purpose is to convey the residents’ needs to the aid organizations. The hope is that Israel will be minimally involved and its important role will be to enable the system to work properly. Foremost among its responsibilities, Israel will retain the job of ensuring that shipments of aid continue entering the Gaza Strip and reaching the refugee camps as needed.

Limitation of the mandate – Humanitarian but not political: It is important to understand that the humanitarian directorates play no political, diplomatic, or security role. Their mandate is solely humanitarian.The limitation on the Directorate’s sphere of activity will also make possible broader cooperation with the local population.

- Splitting and zoning the Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip will be split and zoned according to the following operational principles:

- Establishing a “perimeter zone” where the IDF will provide defensive security: the IDF will play no role inside the camps. Its presence in the zone will serve to prevent Hamas and other terrorist organizations from entering and assuming control. Nonetheless, it is important to note that the IDF will be free to operate throughout the Gaza Strip, including inside the camps, for purposes of counter-terrorism if necessary.

- A system of corridors: Establishing a system of lengthwise and crosswise corridors that will divide the Gaza Strip and deny power to Hamas, like the Netzarim Corridor which isolates the northern Gaza Strip from the other parts and impedes Hamas from entrenching its power in the north. Such a system of corridors will oblige the residents who wish to travel from one part of the Gaza Strip to another to pass through an IDF monitoring system. The system of corridors will be helpful to the IDF’s perimeter defenses and to the prevention of significant infiltration by Hamas forces into the area of IDP cities, thus ensuring them conditions of personal safety and relatively smooth management of the humanitarian campaign.

Districting: The current situation in the Gaza Strip — Approaching territorial separation

A look at the current situation in the Gaza Strip indicates gradual but intensive IDF activity throughout the Gaza Strip with the intent of establishing territorial separation de facto. The policy could be called “districting,” or “engineering a change on the ground.” It lays the foundation for implementing a concept of the future, by engineering certain alterations in the field.

The Gaza Strip does not currently exist in its previous form. In practical reality, what exists is a series of separately controlled regions.

- The Netzarim Corridor: From a dirt road at the start of the war, the Netzarim Corridor has expanded to cover a width of 7 km efficiently separating the northern and southern Gaza Strip.

- The Philadelphi Corridor: Since capturing the Gazan–Egyptian border in May, the IDF has strengthened its control of the route and has established an infrastructure, paving a road and maintaining a continuous military presence. The IDF is estimated to control a width of hundreds of meters along the southern border.

- Perimeter: There are now hundreds of meters of perimeter dividing the Gaza Strip from the neighboring Jewish communities. Since the start of the war, work has been in progress on evacuating the few buildings and infrastructures that were in this area — the clear majority of which was farmland — and creating a buffer zone. Elements from the IDF and from the civilian sector have been demanding establishment of a one-kilometer buffer zone, on the Gaza Strip side, since the start of the war.

Crossings

The plan must also rely on the operation of a set of crossings between Israel and the Gaza Strip.

- The Erez Crossing, which also serves for pedestrian traffic and the delivery of goods;

- The Karni Crossing, including the old crossing for fuel in the Karni area;

- The Sufa Crossing, which has served in recent years for the passage of aggregates and building materials;

- The Kissufim Crossing; the Kerem Shalom Crossing, which has been serving for some months as an alternative to the Rafah Crossing for the entry of goods into the southern Gaza Strip.

Israeli supervision of the anchorage at the Gaza Port area — near the site where the Americans set up the floating dock — will also assist in Israel’s future control over the Gaza Strip, by helping to secure shipping lanes that will be drawn and controlled from a command center to be set up at Ashdod Port, turning the anchorage into a “branch” of the Israeli port.

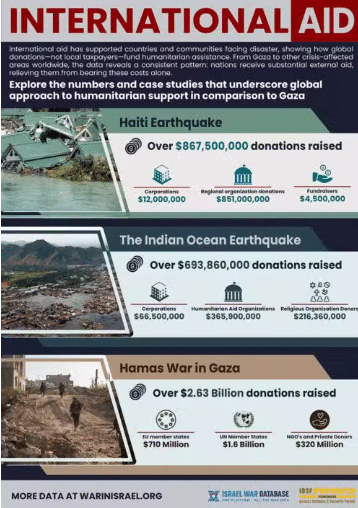

- Costs — Not at the expense of the Israeli taxpayer

From among all the alternatives that have been suggested, the proposed model for a Humanitarian Directorate is also what will impose the lowest financial burden on the Israeli taxpayer.

International aid organizations assume the budgetary and operational burden of distributing humanitarian aid in disaster areas worldwide. Similarly, Israel is not funding the humanitarian aid budget in the Gaza Strip today.

We acknowledge emphatically that according to a certain contention, the financial outlays devolving upon the State of Israel in any scenario where it controls Gaza, including a case of controlling nothing but humanitarian aid there, will be heavy and even reach the tens of billions of shekels a year. We adjudge that contention to be baseless.

We will be examining the various participants’ financial outlays in humanitarian aid for the Gaza Strip and in test cases from the world’s disaster areas.

In the case of Gaza and in the other cases, broad participation has been enlisted internationally from aid organizations, human rights organizations, states, private donors, corporations, financial bodies, and other sources who have contributed many billions to humanitarian aid. The Israeli taxpayer will not bear the expenses of humanitarian aid.

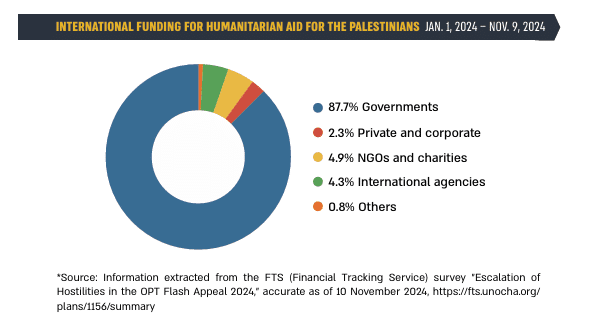

The Gaza Strip — Financial outlays on humanitarian aid, October 2023 – October 2024

Between January and October 2024, the international financial aid for the purchase of humanitarian supplies to benefit the Palestinians (in Judea, Samaria, and Gaza) amounted to roughly 2 billion dollars. In comparison to previous years, when donations amounted to roughly 1 billion dollars, the war generated a significant wave of international donations. A clear majority of the aid was donated by the world’s governments, led by the USA, the EU, Germany, and the UAE. Additional donations were received from a number of governments, mostly in Europe and the Arab world; from charitable foundations; from international aid organizations such as WFP and Oxfam; and from private donors and other organizations. We stress that the Israeli taxpayer is not included in the list of donors.

International funding for humanitarian aid for the Palestinians | Jan. 1, 2024 – Nov. 9, 2024

87.7% Governments

2.3% Private and corporate donors

4.9% NGOs and charities

4.3% International agencies

0.8% Others

Hostilities in the OPT Flash Appeal 2024,” accurate as of 10 November 2024, https://fts.unocha.org/plans/1156/summary

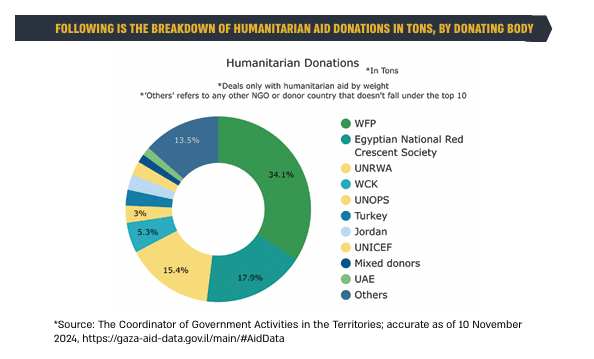

Following is the breakdown of humanitarian aid donations in tons, by donating body:

* Source: The Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories; accurate as of 10 November 2024, https://gaza-aid-data.gov.il/main/#AidData

Remarks, advantages, and disadvantages

Remarks:

- Applying the model of a humanitarian directorate without political authority, as described above, will — in contrast to a model of martial law, for example, or any model of Israeli rule — maximize the chances for continued cooperation with the various players in all the categories mentioned above.

- The proposed model can minimize the theft of aid by Hamas, bring maximum aid to the population while increasing efficiency, and afford the aid workers more safety. All this will lead, in turn, to an increase in the aid actually reaching the residents.

- Administrative costs — Whereas martial law requires the establishment of an entire apparatus of authority — from the level of management and political guidance to the level of operations, and involving the costs of implementation on the ground — the Humanitarian Directorate is a very lean model. The Humanitarian Directorate requires only the capability of coordination, and Israeli authority will remain minimal during the interim phase. Thus, for example, Israel will not be responsible for trash collection but will active in coordination, facilitation, and assistance.

The model’s advantages

- This is a recognized international model backed by broad experience — Many IDP cities have been constructed around the world over the years — for example, in Pakistan, Turkiye, Uganda, Lebanon, and Jordan, as well as elsewhere.

- International and local resistance is minor — Applying the model of a humanitarian directorate without political authority, as above, will — unlike the military administration, for example, or any model of Israeli authority — maximize the chances for continued cooperation with the various players in all the categories previously mentioned. The Directorate, having (as noted) no political authority, will be defined as temporary and will involve the local population, as well as the aid organizations, in the work of administration.

- Minimizing looting by Hamas — Efficiently delivering the maximum amount of aid to the population and increasing the safety of the aid workers.

- Finding and developing local elements with the potential to cooperate constructively in the future as well — The local forces that will be deployed as representatives inside the IDP cities may potentially assume a more active role in the Gazan leadership of the Day After as well. Today Israel has difficulty establishing ties with elements that are able and willing to assume leadership, are considered legitimate in their locality, and are opposed to or independent of Hamas. Because Hamas has been totally and cruelly dominant in the Gaza Strip, such voices have refrained from presenting themselves and in the rare cases when they did receive publicity, those same possible alternative elements met fierce and even murderous responses from Hamas.1 In this connection, the IDP cities and the need for local leadership to administer humanitarian tasks can constitute an opportunity for establishing such ties.

- Denying power to Hamas — It is important to remember this at every step of the way, because every part of the program has the objective of removing another link from the chain of powers possessed by Hamas. The growth of a new local leadership, detached from Hamas, is an important part of the program.

- The State of Israel is confronting heavy international pressure to return the Palestinian Authority to Gaza and establish a Palestinian state in the context of a “two-state solution” as the “only possible” solution to the conflict. For want of available alternatives in Palestinian society today, as well as a lack of imagination and patience, the countries of the world believe that strengthening the PA is integral to the path that will finally lead to the Palestinian state that they wish to promise their home constituency. In the Gaza Security and Recovery Program that we have composed, we deal at length with those two issues. First, why the PA is no partner for any plan that enables a peace-loving state to be established alongside Israel but is rather a feeble, corrupt supporter and funder of terrorism which cannot be returned to Gaza at this point and is definitely not wanted there either.2

The second question has to do with a Palestinian state. Here too, our paper deals at length with a long-term possibility envisioning a multi-stage program which, if implemented patiently and successfully, could bring the ascendency of a different Palestinian leadership, one uninfected by hatred and by support of terrorism. A generation inculcated with different principles and embodying different possibilities. The objectives of all the participants from western nations, from moderate Sunni Arab nations, and from Israel are similar. A benign Palestinian entity, one that does not dedicate itself wholeheartedly to the endless cycle of violence and bloodshed, to plundering humanitarian aid, and to no building of any beneficial economy or social structure. A benign, stable entity that will build an economy and cooperate with the West and with the moderate states. Our program seeks to create all that, over time. First by implementing the interim phase and then by implementing the full Gaza Security and Recovery Program.

Disadvantages of a military administration versus the Humanitarian Directorate

- The phrase “military administration,” even if referring to a temporary humanitarian mechanism, is loaded with negative connotations for a range of relevant target audiences — for the Palestinian population, and for potential partners both in the West and in the Arab world. In addition, it is reasonable to expect that re-institution of martial law in the Gaza Strip would be opposed by more than a few Israelis, for a variety of reasons. Most importantly, the lack of international support would leave Israel to shoulder all the expenses, would increase the pressure on Israel to leave Gaza or to agree to conditions unfavorable to Israel, and would further the delegitimation campaign against Israel on the grounds of “military occupation.”

- Legal complexities could gradually embroil the implementation of a military administration. A Humanitarian Directorate can be gradually instituted in any number of steps, as long as it is possible to set up one IDP city after another. The quick establishment of a military administration is a challenge, because of the legal complexity, and therefore it may be assumed unlikely to come about speedily and unreasonable to foresee before the end of the intensive warfare throughout the Gaza Strip.

- Temporariness — A temporary model may turn permanent over time. However, if the intent is to find an optimal model for the interim phase, then the Humanitarian Directorate will naturally advance Israeli interests much better than a return to military administration would.

Appendixes

Appendix A

UNHCR’s procedures of evaluating the humanitarian needs of a population in disaster areas

For a summary of the agency’s NARE procedures, use the following link:

And below is a link to the agency’s complete guide to the NARE procedures for assessing a population’s needs:

Appendix B

The successful Iraqi case study for the UNHCR procedures

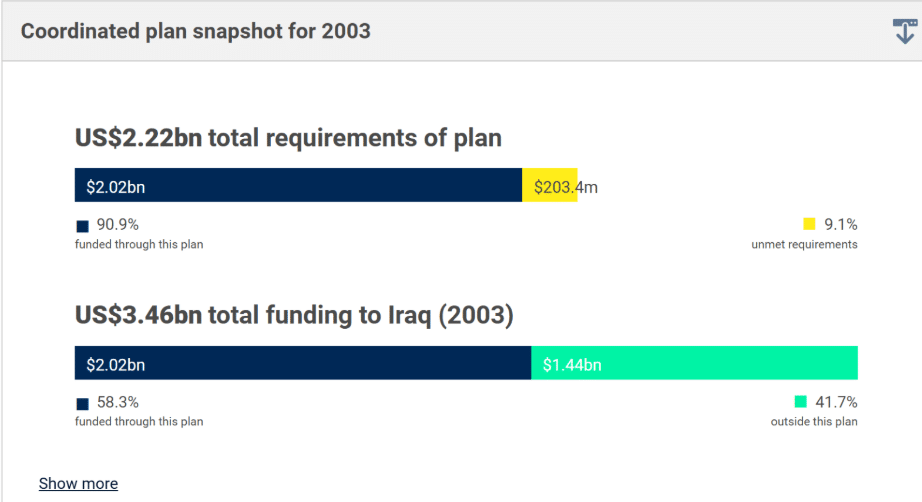

The willingness of Arab states to host large numbers of refugees with limited rights has been illustrated by their response to the Iraqi refugee crisis since 2003. The Iraq response has been highlighted as a testing ground for UNHCR’s new approach to protecting and assisting urban refugees, and has been thoroughly profiled elsewhere. In general, UNHCR’s experience has been regarded as a relative success, in that protection space was expanded beyond early expectations, especially in view of the fact that the key host states are not parties to the Refugee Convention and are opposed to local integration of refugees.

Although governments did open some services to refugees in the fields of education and health, the response to the Iraqi refugee crisis was in others ways to strengthen the preexisting UNHCR surrogate state. UNHCR experimented with new means of directly delivering food and monetary assistance to needy refugees and carried out reception and registration. Whether services were delivered by governments or UNHCR, much of this success has been attributed to the high interest of donors and resettlement states in the Iraqi refugee issue, allowing UNHCR to mobilize considerable resources for responsibility sharing3.

Source: FTS, https://fts.unocha.org/plans/122/summary

Appendix C

International financial mass donations for disaster and conflict areas

Executive Summary

In the relief efforts after major natural disasters and in recent conflict zones, a number of different types of donors have contributed. These generally have included national governments, regional organizations, major corporations and individual donations, donations from religious organisations and humanitarian aid organisations.

Given the estimates that any involvement in Gaza would entail massive expenditures for the Israeli tax-payer, it is important to underline that in none of the following cases did the expenses related to humanitarian aid borne by the disaster-affected country.

The following What follows is an overview of the the donors to the relief in the following major conflict areas and natural disasters: – t

- The Turkey-Syria earthquake in 2023, t

- The Russian invasion of Ukraine (2022-),

- Haiti earthquake relief in 2010 and t

- The Indian Ocean Earthquake in 2004.

Turkey/Syria earthquake in 2023 – Humanitarian Response

National Governments and Regional Organizations

A number of national governments contributed to the relief. Regional organizations also included: ASEAN, the Arab League and NATO.

Humanitarian Aid Organisation Donations

Major humanitarian donors to the Turkey-Syria earthquake relief in 2023 included the Norwegian Refugee Council, Oxfam GB, Syria Relief, the World Health Organization and World Vision International. Various UN programs donated including United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East.

Corporate Donations

A number of corporate donors made sizable contributions. These included:

- Kraft Heinz who donated $500,000 through the Red Cross to support humanitarian aid efforts in Turkey and Syria.

- Starbucks gave $1 million to nonprofits focused on providing immediate relief and aid.

- Boeing gave a $500,000 donation through the American Red Cross and match dollar-for-dollar donations from employees.

- Uber made a $100 million donation to local nonprofit Ahbap.

Russian Invasion of Ukraine

Major humanitarian donors to Ukraine have been:

ActionAid International, Catholic Relief Services, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, the International Rescue Committee, Oxfam, the Polish Red Cross, the Salvation Army and the Slovak Humanitarian Council.

Corporate donations

Boeing, Visa, Mastercard, IBM, Johnson and Johnson, Pfizer, Caterpillar, Delta amongst other major corporations all committed humanitarian contributions at the U.S.-Ukraine Business Council in Washington D.C., on Monday, March 14, 2022. Boeing committed US$2 Million to support the humanitarian Response in Ukraine. The Visa Foundation provide a $2 million grant. Mastercard announced a $2 million contribution to the Red Cross, Save the Children and their own employee assistance fund for humanitarian relief.

IBM employees around the world were encouraged to continue making donations to the International Red Cross towards humanitarian relief in Ukraine. Pfizer provided a total of $2M US in humanitarian grant funding to UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), American Red Cross, International Medical Corps and International Rescue Committee (The IRC) through The Pfizer Foundation*.

Haiti Earthquake relief 2010

Regional organization donations

The European Council and its member nations later announced more than €429 million for Haiti relief efforts. The EU pledged €122 million in humanitarian assistance. The Union of South American Nations also pledged US$300,000,000 to help rebuild Haiti in the long term.

Corporate Donations

In coordination with the Kenya Red Cross, Kenya Airways—the country’s largest airline and flag carrier—raised money for earthquake relief efforts by collecting donations on local and international flights. Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, an international pharmaceutical company headquartered in Israel which is the world’s largest generic drug manufacturer, donated over $7 million worth of medication.

Several days after the earthquake, Deutsche Bank announced that it would donate 100 percent of net US agency equity trading commissions on January 15 to the humanitarian cause. The initiative raised approximately US$4,000,000. Nestle gave $1,000,000 in bottled water donations.

Worldwide Fundraising Events and Donations from Individuals

Organisers of the 2010 Australian Open, a day prior to the tournament opening, held a quickly organised event called “Hit for Haiti” conceived by tennis star Roger Federer to raise funds.

Jennifer Aniston announced a donation of US$500,000 to Doctors Without Borders, Partners in Health and Americares. Leonardo DiCaprio donated US$1,000,000. Queen Elizabeth II made a donation to the relief effort and issued a personal message of condolence to the President of Haiti. Tiger Woods donated US$3,000,000.

Response by online communities

Various online communities raised considerable funds. Following the earthquake of January 12 2010, Users of online community Avaaz had raised over US$800,000 as soon as January 16. Reddit users had raised over US$178,000 by February 15 of that year.

Indian Ocean Earthquake 2004 Major Donors

National Governments and Regional Organizations

National Governments and regional organizations including the African Union, and the European Union to the relief efforts. The EU provided immediate emergency aid of €3M (US$4.1M) for victims to meet “initial vital needs”, with more substantial aid (€30M) to be provided later. This is separate from contributions by individual member countries. The African Union Commission Chairman Alpha Oumar Konaré announced that the organisation would put forward US$100,000 towards disaster relief.

Religious Organisation Donors

Jewish Organisations

Religious organizations provided major donations and this group included numerous Jewish organisations. The American Jewish Committee established a Tsunami Relief Fund, and initially allocated US$60,000 out of its own account. It subsequently raised an additional US$450,000. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee collected more than US$2M in individual contributions to the organisation’s non-sectarian South Asia Tsunami Relief mailbox. With US$3.25 million raised, The American Jewish World Service focussed efforts on providing direct material relief to the poorest families in affected areas, including providing food, water storage containers, cooking supplies, blankets and temporary shelters and partnering with Direct Relief International to provide immediate shipments of basic medical supplies, water purification materials and oral rehydration therapies to the heavily affected communities in India and Sri Lanka. Just 24 hours after United Jewish Communities Federation of Greater Toronto opened its Tsunami Relief Fund, the fund had raised more than C$150,000 from over 500 donors. The United Jewish Association commissioned two quarter-page ads in the New York Times, raising at least US$500,000 in support of South Asian Tsunami victims. The British group, World Jewish Aid, initially providing £25,000, working with partners on the ground in India, Indonesia and other affected areas so to realise where their aid should be directed best.

Other religious organisations

Catholic Relief Services mounted one of the largest responses in its history – a $190-million, five-year relief and reconstruction effort that would help more than 600,000 people. CRS had more than 350 employees working in the hardest-hit areas in India, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. Islamic Relief Worldwide increased its emergency appeal to US$5M. This included an initial US$270,650 for relief and rehabilitation intervention in the region, and US$27,000 to meet the immediate needs of victims in Sri Lanka. The Mennonite Central Committee responded with more than US$15 million in immediate and long term assistance[153] They completed their disaster response in Indonesia in July 2008 after spending US$10 million for recovery in Aceh.

Humanitarian Aid Organizations

Médecins Sans Frontières dispatched 32 tonnes of relief supplies to Sumatra. Medical and assessment teams were sent to many of the affected areas. In Geneva, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies appealed for CHF 7.5M (about US$6.6M) for “immediate support” to an estimated 500,000 survivors.

Within days of the tsunami, Mercy Corps rushed emergency responders and relief supplies to the devastated coastal region of Aceh, Indonesia – the closest landmass to the epicenter of the quake. Mercy Corps delivered emergency food to over 288,000 survivors, hygiene supplies to more than 253,000, and building materials to construct more than 500 temporary shelters. Cash-for-work programs cleared debris from over 13,000 hectares of public and agricultural land and 50 kilometers of road, and got money flowing back into the decimated local economy.

In India, Oxfam directed its aid to four regions including the communities of Cuddalore, Nagapattinam, Kanyakumari, and along the southwest coast of Kerala. The agency put together a US$13.3M plan to provide immediate relief for people in those regions as well as offer them longer-term assistance to help rebuild their lives and livelihoods. The plan included digging latrines, repairing water sources, and providing temporary shelter for up to 60,000 people, as well as distributing essential household items such as soap, buckets, and coconut oil. In Sri Lanka, Oxfam was appointed as a key organisation to provide clean water and sanitation facilities in the northern part of the country. Staff members in four field offices

World Vision completed the final stage of its three-year Asia Tsunami Response (Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka, Thailand). The US$346.5 million-organization’s largest relief effort-program encompassed emergency relief, community rehabilitation (including child-focused programs), livelihood recovery, and infrastructure rehabilitation. Gender, protection, conflict sensitivity, HIV/AIDS and advocacy were cross-cutting components of World Vision’s response.

Corporate Donations

Again, a number of major companies made donations to the relief effort.

These included: Pfizer who made a total US$35M contribution ($10M cash; $25M medicines), Deutsche Bank (US$13M), Coca-Cola (US$10M), ExxonMobil (US$5M), Microsoft (US$3.5M).

To conclude

All of these incidents had the support of national governments and varied intergovernmental regional organisations. Religious communities and corporations make substantial contributions, whether to the recovery following natural disasters or for conflict recovery efforts, such as in Ukraine.