Today’s tour follows one of the biggest tragedies of Israel’s War of Independence – the fall of the La’med Hei Platoon. For decades, this sad story has been stoking heated debates regarding the necessity, the preparation, the chosen route, the execution and the selection of the platoon members of this operation.

Type of tour: by car

Estimated duration: 4-5 hours

Difficulty: easy

Starting point: Tel Beit Shemesh (Waze: Tel Beit Shemesh)

Gush Etzion: a thorn in the flesh of the Arabs

In order to understand the battle legacy of the La’med Hei Platoon, one must first understand the importance of the Gush Etzion settlement bloc in the War of Independence. Gush Etzion lies south of Jerusalem and Bethlehem, and is situated on the main road to Hebron. This meant that the Jews could launch attacks on Arab Jerusalem from the south, and disrupt the ability of the Arab population to travel between Hebron and Jerusalem. The settlement bloc consisted of four communities: Kfar Etzion, Massuot Yitzhak, Ein Tzurim and Revadim. Due to its strategic location, the bloc was a thorn in the flesh of the Arab enemy, and the Arabs were determined to remove it, at any cost.

Gush Etzion’s main vulnerability was its distance from any military aid. The nearest Jewish military force was located in Jerusalem, and the next outpost was in Kiryat Anavim, to the west of the city. Apart from Jerusalem, the closest Jewish settlement was the Hartuv township. Remember this name as it is to play a crucial role in our story.

As part of their scheme to eliminate the hindrance of the Jewish bloc, Arab forces lay siege to the settlements, which necessitated the transfer of supplies from Jerusalem. The supply convoys to the bloc were routinely attacked by the hostile Arab forces, and the convoy leaders suffered heavy losses. Aside from scant isolated victories, the bloc’s situation became dire. It was clear that without the help of British escort forces, convoys could not make it through to the Jewish settlements of Gush Etzion. The British, however, were not enthusiastic, to say the least, about escorting the convoys as they were in the midst of withdrawing from then Palestine.

Hence, at a certain point, a decision was made to aid Gush Etzion by sending reinforcement to boost the bloc’s defense, and to bring to it as much ammunition and equipment as the soldiers could carry on their backs. The mission was assigned to 40 select fighters, commanded by Danny Mass. The platoon, named the La’med Hei referring in numerology to its 40 members, was equipped with a large quantity of weapons and medical supplies, but did not carry any communications, which would prove to be detrimental.

From 40 to 35 – trouble at the onset

Departure was set to January 14,1948, eight o’clock in the evening. However, after various delays, and the realization that the force had only 38 rifles, departure was delayed to 11 o’clock at night, minus two soldiers, who were dropped from the mission due to the shortage of guns.

The 38 soldiers were driven by bus to the point of departure, however, a short distance from the base, found that the road was blocked with boulders. They decided to disembark and set out on foot at an earlier than planned point in the Refaim ravine. After a long hike, the force fell into discord regarding the right route they should be taking. At about three o’clock in the morning, shots were heard and the force was concerned that it was discovered and decided to head back. At five o’clock in the morning the force arrived back at the point of departure in Beit Karem in Jerusalem.

As protocol would not allow to return to the original rout the day later, and as the shots heard the previous night caused concerns that they would walk into an ambush, it was decided to use an alternative route. Again there were disputes on the best route and eventually it was decided to depart by foot from the Jewish township of Hartuv, which is relatively close to Gush Etzion.

The route chosen led from Hartuv westward, circumventing the British police station in Artouf (today Beit Shemesh), and the Arab village of Dir Aban (today Moshav Machsiya), and then head south through what is today Moshav Yishi, and through the ravines of Biet Natif and Surif, and finally climb to Gush Etzion. The length of the entire route was only 26 kilometers, with a 600-meter climb, The 40 soldiers departed via bus to Hartuv but again, a shortage of guns left two behind (Yaakov Zarhi and Yigal Butrimovich).

Departure was scheduled for seven o’clock in the evening, with the aim of reaching Gush Etzion around three o’clock in the morning. But as expected, dinner was delayed, preparations were prolonged, and only on Thursday, January 15, at eleven o’clock at night, the platoon set out.

Commander of the Hartuv force, Rafael Ben Aroya, suggested that Danny Mass postpone the departure to the next day because he thought they would not be able to reach Gush Etzion during the nighttime under the cover of dark but in broad daylight. Danny Mass determined that it was possible to cross the territory of both hostile villages of Surif-Jaba under cover of the dark. After that, they would only have five kilometers left on a strenuous ascent uphill, but they will already be in a topographically advantageous territory Arab population and near the Jewish settlement bloc.

Thus the platoon set out, circumventing Tel Beit Shemesh from the west. One of the fighters, Israel Gafni, sprained his ankle at the Einot Dekalim spring. The force continued east to the area which today is an abandoned settlement. The injured soldier slowed the force, and Danny Mass decided to send him back to Hartuv along with two other soldiers (Uri Gavish and Moshe Hazan) to assist him. They went straight back to Hartuv.

Hence, of the original 38 who set off on the mission, 35 were left to traverse difficult terrain, to say the least, with a large quantity of heavy equipment, and at least another five hours of hiking. Yisral, Ori, and Mosheh are the last Jews who saw their comrades of the La’med Hei platoon alive.

From this point until the discovery of the bodies of the 35 soldiers, it is not known exactly what had occurred.

First stop of the tour: Beit Shemesh observation deck

It would have been fitting to begin the tour at the site of the ruins of Hartuv, however, unfortunately the site is derelict with no proper access. We will try to see what we can from the nearby road. Coming from the direction of Sha’ar Hagai, a few dozen meters after the Hartuv interchange, right in front of the Hartuve greenhouses, looking to the right offers a glimpse at the ruins of buildings and a blue sign of the Council for Conservation of Sites. These are the remains of the Hartuv settlement.

Passing the ruins of Hartuv, we can see on the left, between the trees, the building that housed the Artouf police station, which is now the Beit Shemesh police station.

We will pass the Beit Shemesh junction and reach Tel Beit Shemesh. The site has a fascinating biblical history, including the story of the return of the Ark of the Covenant from the Philistines back to Israel. We will visit the observation deck.

At the top of the hillock there is a modern concrete observation deck. From here, looking north, we can see the Sorek stream flowing below. The Beit Shemesh–Tel Aviv railway is visible as well. Across the tracks adjacent to the road is a grove partially hiding the remnants of Hartuv, the place from which the La’med Hei platoon embarked on its mission. They circled the hillock, on which we are standing, and walked towards Moshav Yeshay, which we can see if we turn our gaze southward. About two kilometers south is the Ein Dekalim spring, where platoon member Yisrael Gafni sprained his ankle.

Second stop: the La’med Hei monument

We will continue driving until we reach the Ella junction, where we turn left onto Route 375 and drive until the entrance to “Netiv Ha-La’med Hei”. Just before the entrance, turn right to the Netiv Ha-La’med Hei monument (write in Waze “Ha-La’med Hei Memorial”).

Kibbutz Netiv Ha-La’med Hei, established in 1949, commemorates the soldiers of the La’med Hei platoon.

The platoon seemed to have navigated well, but the delays proved to be detrimental to them. It was towards six o’clock in the morning, on Friday, 16.1.1948, when the sun was already shining, that the platoon, overburdened with heavy equipment, found itself caught between the two Arab hostile villages of Surif and Jaba’, in a vulnerable position – the worst possible scenario, which led to their discovery in a particularly exposed position.

The account of the discovery of the force and the ensuing battle is based on Arab sources, information from the Haganah’s intel unit, and most of all on the testimony of the British commander of the Hebron police at the time, Hamish Dugan.

As mentioned above, apparently around six in the morning the force patrols were discovered. The version that was publicized sever days after the battle was that is that the patrol encountered an old Arab shepherd and spared his life. The Arab fled, alerting the people of Surif, and thus the battle began. However, Testimonies from Arab sources indicate that the patrol in fact encountered women at the river drawing water or collecting fire wood, and they were the ones who alerted the villagers. The patrol reported the encounter to Danny Mass, who decided to forge forward at a quicker pace before the villagers issued a “Fazah” (an alert conveyed by shouts from one post to another throughout the village). He believed that the more territory the platoon covered, the better its topographical situation would be, and it is possible that if they had been close enough to the Gush Etzion settlements, they would have received help from there.

News of the Jews roaming the area reached Ibrahim Abu Dia, who was the deputy of Abd Qader al-Husseini’s, one of the leaders of the Arab forces in the Jerusalem area. Abu Dia was in Surif as part of commanders’ training for the “Holy Jihad” militia. Meaning that the platoon faced skilled fighters with training and experience, and not just an angry mob of villagers.

Abu Dia sent several fighters to engage the La’med Hei force with suppressive fire, but between eight and eleven o’clock in the morning, the platoon advanced to the area of today’s Jaba’ checkpoint, from where they descended northward to Nahal Etziona, in order to disengage with the attacking force. The first phase of the battle had ended, but in the meantime the Arabs had seized command of the hills north of the possible retreat route. It is unclear why the force did not split up or wait until the cover of dark to extricate themselves. Some speculate that the fighters did not know they were surrounded by thousands of Arabs.

Before moving on to the next point on the tour, we will visit the monument itself, which has an audio guide.

The monument is built of 35 concrete pillars representing the 35 fallen, and has an unfinished path, symbolizing the incomplete mission, and a stone wall with the names of the fallen.

Standing at the monument, we will look south (to the road from which we came) and look east (to the left), where beyond the hills is the village of Surif. Right below us, we can see the route the fighters took on their way to the village. This view from the observation deck clearly illustrates the topographical disadvantage in which the platoon found itself against the Arab forces.

Third stop: The La’med Hei lookout

From the monument we return to Route 375, turn left and at the Etziona junction turn right to Route 367 on which we will drive 6 km to the La’med Hei lookout (Waze: “La’med-Hei Lookout”).

We return to the plight of the platoon, who managed to evade their attackers in the first part of the battle. At around 14:30 in the afternoon, commander Danny Mass decided to climb Hill 573 (later known as “Battle Hill”). Until today, it is not known why Danny Mass decided to ascend this hill; Perhaps he hoped to break through the siege and go northward or improve the platoon’s position to continue on the route to Gush Etzion. While climbing, the force was sighted by the Arabs, who were already in control the surrounding elevation points, and an exchange of fire began. At that point, several fighters were already wounded while climbing the hill.

When the platoon reached the top of the hill, the fighters discovered that they were surrounded by an angry Arab mob. The Arabs fired at them from several surrounding points, but mostly from Hill 603, which dominated the assault on Battle Hill. The Arabs charged wave after wave, but were repelled again and again – until the platoon ran out of ammunition. According to testimonies, the last fighter was killed before dark, around five o’clock, when he threw his last grenade at the attacking Arabs.

As mentioned, the platoon set out on its mission without taking communications, thus, it was unknown what was happening to the platoon in real time. The Gush Etzion communities knew that the platoon was on its way, but when it didn’t arrive in the morning, they sent a message alerting there was a problem. At around one o’clock in the afternoon, members of Massu’ot Yitzhak moshav heard shots coming from the direction of Zurif, but did not attribute the shots to the platoon. Light planes patrolled the area in an attempt to find the platoon, but found nothing (it is likely that the platoon members were hiding in a cave or crevice at the time and were not seen by the pilots). Patrol forces were dispatched from Gush Etzion in an attempt to find the platoon – but to no avail.

In the afternoon of Friday, 16.1.1948, rumors reached the Hebron police that there was “trouble” in Zurif. Station commander Hamish Dugan went out to the area, but found nothing out of the ordinary. The next day (17.1) he went to the Battle Hill, where he found the bodies of the Jewish force. News of the discovery of the bodies were passed on to the Haganah headquarters in Jerusalem. Dogen began collecting the bodies. In the evening he left, after the Arabs had promised not to desecrate the bodies. According to his own account, he promised 500 mils for each body.

On Sunday (18.1), Dogan returned to the village, where he learned of a “Jewish attack” on Zurif; These were two British soldiers whom the villagers considered Jews, and were about to kill them. Dogan saved the British soldiers from death. Rumors of the “Jewish attack” spread quickly, and the body collectors broke their promise, mutilating the bodies.

The bodies were transferred to Kfar Etzion. The next day, several of the deceased’s parents arrived to identify their loved ones, and Rabbi Aryeh Levin prepared the bodies for burial in Kfar Etzion.

In October-November 1949, Rabbi Shlomo Goren piloted an operation to retrieve Jewish war casualties buried in enemy territory. 323 fallen soldiers were exhumed and buried in a mass ceremony on Mount Herzl on 17.11.1949. Among those were soldiers of the La’med Hei platoon.

Back to our tour: from the lookout we will view the battle hill, and understand the topographical disadvantage the platoon was trapped in, surrounded by enemy forces positioned on the surrounding hills.

Now is the time to listen to Haim Guri read the poem he wrote the day after the battle: “Here Lie Our Bodies” (starting at minute 04:11)

The poem:

Fourth stop: the lone oak tree

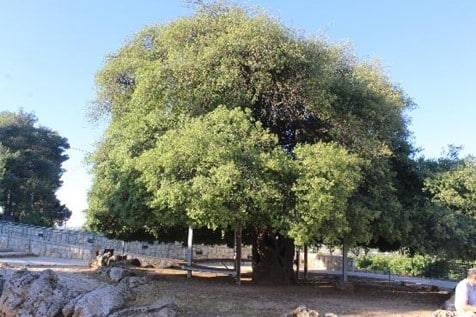

We’ll set out in the car and turn left onto Gush Etzion, towards the lone Oak (Waze “The lone oak”). This single oak is an ancient tree that was at the center of the old Gush Etzion community bloc. After the fall of the bloc, the people of Gush Etzion used to stand at Mevo Beitar or Nes Harim and look out onto the oak. It signaled their longing to return to Gush Etzion. After the Six-Day War, the settlement of Alon Shvut was founded, its name roughly translating to “The return to the oak” and the tree being the symbol of the settlement. At the site of the oak, we can see the monument that was erected in memory of the fallen of Gush Etzion.

The large plaza near the oak is where we end our tour in the footsteps of the heroes of the La’med Hei platoon.

At the site of the lone oak we will discuss the army values at the core of the IDF, which were present in the story of the La’med Hei platoon:

- Duty and courage: Commander Danny Mass showed unwavering commitment to the mission. Even when the departure was delayed by a day or hours – he still set out, placing the mission above all. Danny Mass had every reason in the world to abort the mission, but he was committed to delivering the critical supplies and equipment so desperately needed by the besieged people of Gush Etzion.

- Initiative and response, unaccepting defeat: more than a few obstacles stood in the way of Commander Mass and his platoon – from the shortage in weapons for his men, faulty transportation, an injured soldier, navigation difficulties, and retreat under fire from an exposed position. Commander Mass did not remain passive, but led the force through every obstacle, took initiative and came up with solutions on the go. Even when the force was discovered by the enemy he swiftly responded, commanding a repel and retreat battle to lead his men to a better position in a challenging terrain.