Between IDSF member Brig. Gen. (Res.) Ari Singer and the Israeli army, the bond was a matter of several decades and it relaxed only two years ago or so. In his last position, he served as commander of the reserves, so he has a deep understanding of the military system in general and of the reserves in specific.

The commander of the reserves is responsible for the reservists in all respects, both within the army and vis-à-vis the government. Where the government is concerned, his position is subordinate to the Ministry of Defense. Where the army is concerned, until recently it was subordinate to the Deputy Chief of Staff but currently it is subordinate to the Adjutant General. Singer believes that the transfer of authority was a mistake. “The reserves fill a central role in the army,” he says. “I hope that as we put the lessons of the war into practice, we’ll understand that the commander of the reserves should be returned into the forum of the Chief of Staff.”

That issue of the commander’s affiliation is not the only thing that’s changed over time. “In recent years, doubts had been brewing as to whether the reserves were necessary. A belief was setting in that we could win our military confrontations with fewer reserve soldiers,” Singer says. “Because of that thinking, the reserves lost some of their standing, their assignments were reduced, and the number of reservists was cut. Now we’ve discovered that the wars have not ended, and everyone realizes that in wartime you need to do even more than beef up the reserve units. The units of the enlisted army itself can’t function without reservists.”

The unbearable easiness of exemption

According to the former commander of reserves, not only must the reserve forces not be reduced, but the IDF’s order of battle must be augmented, both in the enlisted army and in the reserves.

Singer suggests a number of ways to make that possible. First, he believes that compulsory service must be lengthened back to three full years. Second, he says that further population sectors should be drafted that are currently not among the ranks. He mentions the haredim, among others, as well as those exempted for various reasons. “Some exemptions are defensible,” Singer says, “but these days anyone who wants one enough can get an exemption from the army. It’s unacceptably easy.”

Another suggestion from Singer is to make a reservist of every discharged soldier. “Today a sizeable fraction of noncombatant soldiers, and women soldiers, are exempted right away from reserve duty. That has to change,” he states. “Even though some soldiers haven’t served in an especially meaningful position as draftees, that doesn’t mean they can’t be placed in an important position as reservists. Many soldiers who served at desk jobs find themselves civilian jobs in engineering and hi-tech, and they can contribute their knowhow to the army. And of course, women soldiers can also continue contributing to the army as reservists.”

When Singer mentions the order of battle, he means not only the enlisted soldiers and reservists, but also the volunteers. He says that the volunteers deserve appreciation but need better organization and firmer obligation. “Right now, you can stop volunteering at any moment; and that’s a problem,” he explains. “It’s as if you started to help an old woman across the street and then decided against it halfway across and left her there alone. It’s impossible to behave like that. If you volunteer, you have to accept a commitment and report for training like the rest of the reservists.”

Changes in reserve duty? Don’t rush to legislate.

Singer is not the only one in favor of augmenting the order of battle. Many ideas are on the table for increasing the number of active IDF personnel. Suggestions include, among others, raising the age of discharge from the reserves and adding days of active duty for all the reservists.

According to Singer, the system of reserve duty needs to be re-evaluated but decisions must not be hasty. “We’re in a state of complete uncertainty, where we don’t know how the conflict is going to evolve,” he explains. “I say to all the decision-makers: ‘Don’t rush to legislate.’ Any change in the law has ramifications many years onward and it’s wrong to make decisions when we’re experiencing an emergency and don’t know how it will end. We need to find temporary fixes for the coming year, and we have the legal tools for doing that. Just now it was decided to add one year to the exemption age, and that was a temporary order. It was a necessary decision. Later, we’ll consider whether we need a lasting raise in the exemption age and for how long we need it.”

Singer stresses that even if it’s decided that the Reserve Duty Law should be changed, it’s important to ensure that it remains fair to the reservists. “The elements of the Reserve Duty Law must be balanced,” he states. “If we take it on ourselves to demand more from the reservists, we have to take it on ourselves to show them appreciation and compensate them fairly.”

Singer adds that compensation should go not only to the reservists themselves but also to their support systems. “The families and the employers of the reservists are also ‘called to duty’ whether they like it or not,” says the former commander. “We have to be sensitive to the families’ needs, and considerate as possible to the reservists, in order to reduce the damage to their personal lives. Besides that, we need to be fair to the employers. We can’t reach a point where employers are absorbing the cost for the call-up of all their workers, because then they won’t want to employ anyone who’s eligible for reserve duty.”

Refusal to serve? Reality shows otherwise.

Since the war of “Iron Swords” started, the reservists have stood at the center of the public discourse and their contribution has been heartily appreciated. It’s almost difficult to recall that only some months ago the reservists were in the headlines for entirely different reasons. During the protests against judicial reform, many reservists announced that they were refusing to report for duty. That attitude of unwillingness aroused much criticism, and great concern gripped the country and its citizens. There was actual fear that the refusals would diminish the presence and the preparedness of the reservists and make Israel’s self-defense more difficult. According to Singer, the fear was disproportionate even before the war, and it proved illusory after war broke out.

“Despite a lot of noise in the media, there were more threats of refusal than actual cases even during the period of protests,” he says. “On October 7, as soon as war was declared, the reservists came to pick up their equipment before they even received the call. In fact, tens of thousands of reservists who were already exempt on account of age returned to serve at their own initiative. I believe that the IDF will need to investigate the way it handled the threats of refusal and to take the lessons into account going forward; but in the current war, the influence was zero.”

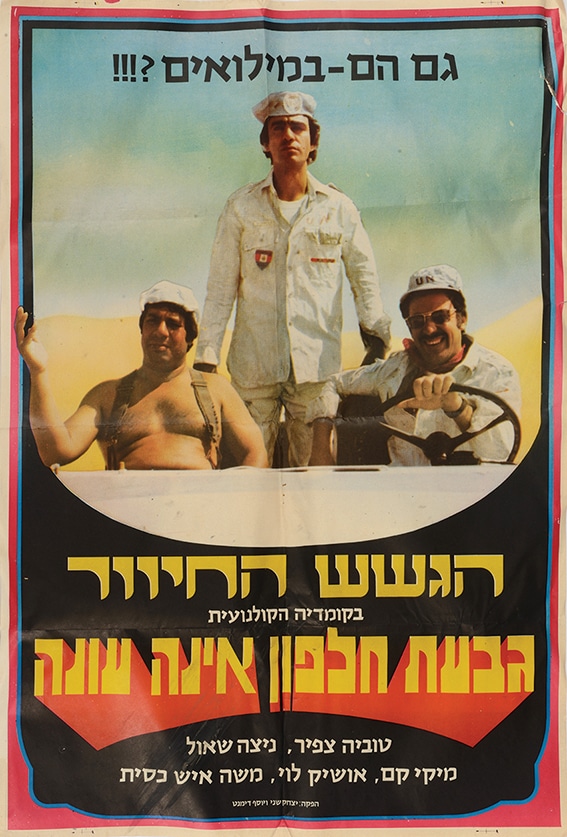

De-Halfonization: No more farcical image

Over the years, along with the internal changes within the ranks of the reservists, a change occurred in the attitude of Israeli society toward the reservists and their professionalism. “I think that respect for the reservists has increased in recent years,” he says. “Once, when reservists were mentioned, people thought of the farcical Halfon Hill movie where the reservists were slackers who cared only about the food and didn’t even know why they were called up to serve. But the system of reserves and the society of Israel have gone through what I call de-Halfonization, and today the reservists are professional, effective, and dedicated. And that’s recognized, even though there’s plenty of room for improvement.”

Singer asks to make some further points about the connection between society and army. He explains that IDF strategy considers the reservists to be delegates in both directions, representing the army to society and representing society to the army. In his view, that’s the best way to phrase the idea. “When I’m asked whether the reservists belong more to the army or more to the society, I answer that they’re the hyphen that links those two. To the army, the reservists contribute the maturity and experience that they accumulated in civilian life. Similarly, they bring back to society what they acquired in the IDF — principled performance, responsibility, and tolerance for sectors who differ from themselves. The reservists, you know, are a mosaic from all over Israeli society, so reserve duty takes you out of whatever bubble you live in and you can develop a real friendship with someone completely different from you, whose ideas are the opposite of yours.”

Much more than a booklet: The importance of IDF values

Not seldom, the reservists’ important contribution to the current war effort comes at a heavy cost. As of today, more than half the war’s IDF fatalities have been reservists. In Singer’s opinion, that painful statistic does not deter the reservists. On the contrary, he explains, “The reservists understand that their task involves values. In their own eyes, each of them is rescuing the country.”

According to Singer, the fighting spirit is not merely born of necessity but built first and foremost on principles. “The IDF spirit is a consistent set of principles obligating everyone who serves,” he says. “It’s a tool of the trade in every way, not just some booklet pushed into the pocket of a recruit.”

Singer believes that just as the principles of the IDF spirit are inculcated, the importance of defending the country should be absorbed by the Israeli public from an early age. “We’re not an army of mercenaries, so it’s important for us to understand why we’re drafted and why we serve,” he says. “The reservists are motivated by a sense of mission, but a mission has got to be a mission for something or somebody. Who sent them on their mission? I’ve asked a lot of people, and mostly they say it’s the commanders or the government. But when I ask the reservists themselves, they almost all say it’s the country. When I’m on reserve duty, I also see myself as on a mission for the State of Israel and for the People of Israel over the generations — both past and future.”