In 2005, the Israeli government approved the National Outline Plan – commonly known as NOP-35. The initiative to put together such a plan was taken by the Ministry of the Environment and led by Yossi Sarid, formerly the Minister of the Environment in the 1992-1995 Rabin government. The plan hardly seems dramatic at first glance. It even seems uninteresting, as it simply aimed to lay out a policy for the concentration of Israel’s Jewish population in urban areas. The plan dissected the country into four zones according to the four major metropolises, around which major construction would be conducted. The “open areas” were designated for preservation. It further set a cap on the growth of Jewish townships and settlements in rural areas.

But in effect, a closer look at the National Outline Plan 35 shows that it is a dramatic plan – already striking roots on the ground – which is detrimentally pushing back the engine of the Zionist enterprise. To understand why, let’s take a step back from 2005’s national outline plan to the partition plan of 1947.

Ben Gurion – why did he agree to the partition plan?

The main claim against the acceptance of the 1947 UN partition plan of the Land of Israel, supporting the establishment of a Jewish state and an Arab state, was that it in effect draws a border that cuts through the country, whereas we aim for sovereignty over the land of Israel in its entirety. David Ben Gurion, Israel’s first Prime Minister, gave the nod to the plan; however, he did not relinquish the Jewish settlements that were left in the Arab part of the map. He argued that with all due respect to the partition plan, borders are set on the ground and not by maps, therefore, each and every Jewish settlement and town by themselves delineate a border with Arab territory. In other words, David Ben-Gurion saw the Jewish settlement of the land as a non-violent means of changing the Jewish state’s position on the ground.

This represesnts an extremely profound rationale. Ben Gurion wisely understood that geography is not an exact science, but rather a social discipline, since what shapes the perception of the reality on the ground is the actions of man. In other words: what shapes the nature of the reality on the ground and a national identity, is first and foremost the civilian claim of the land. A homeland is not an abstract event but rather an amalgamation of actions on the land, by the people of that land. The implication of this concept is clear: Ben-Gurion’s administration endeavored to disperse the Jewish population throughout the entire country.

Sadly, recent administrations undertook the exact opposite: not only do they not promote the widespread settlement of Jews across the country, but they take practical steps to stymie such enterprises. An example of this can be seen in the apartment towers that are growing in Ofakin, Netivot and Be’er Sheva. This policy, deeply rooted in the National Outline Plan 35, put forth two main arguments, which will be discussed in the following section.

Development & Ecology: The Fundamental Misconceptions in the Perception of the Urban Development Vision

The first main argument at the foundation of the urbanization concept goes back to the issue of development. It states that Zionism is not measured by real-estate alone, but also in economic strength and military power, that are dependent on industry. Centralization rather than dispersion is needed in order to development said industry. At the base of this claim is a bourgeoise perception according to which the territory we already have is sufficient, and now we must cultivate and develop what already exists.

The second main argument in favor of this policy is the ecological view, wherein an entire town or city can be rehoused in high-rise apartment towers, thus, preserving natural open land that is important for the ecology.

In a manner consistent with a two-pronged position, the urban development vision has two inherent misconceptions. The fallacy of the first claim is the illusion of stability. Similarly to riding a bike, a land dispute cannot be inert – you either go forward or you fall. Reality demands movement and energy to preserve itself. Stability is a bourgeoise delusion structured upon a misconception of a fixed equilibrium of forces in a given struggle.

In reality though, the Jewish people are in a constant battle against those who champion claims of indigenous rights in the land. When we say “the populated areas we have are sufficient”, we mistakenly take for granted that the open natural areas remain just as they are. But in effect – we are leaving them up for grabs for elements who have never given them up.

This is also the root of the misconception inherent in the second – ecological – argument, which assumes that areas where no Jewish construction takes place – remain open natural habitats. It disregards designs on part of other elements in the area, which on their part, continue to build and expand. The romantic fantasy of ecological preservation cannot hold water in reality because the simple truth is these “natural” spaces are being destroyed in a far less controlled manner, by those jostling with us for the control over territories.

In other words, the problem with the urban development policy is that it abandons Israel’s rural areas to be snatched by the anti-Zionist forces at be, which are not acting unwittingly and which are intentionally striving to undermine the governance of Israel in order to destabilize it, thus overtaking territories over which they have no indigenous claim, and producing a fabricated ethnic claim to territory, or irredenta.

Irredenta: Dangerous Activity, Which Only the Settling of the Land Can Stop

Irredenta is activity on part of an ethnic minority withing the territory of another nation, aiming to ultimately be annexed by a neighboring state, in which it is an ethnic majority. It is important to note that this is not a matter of obtaining the host country’s citizenship but an active effort to take over its land, and to annex those territories – along with its residents – to the neighboring country.

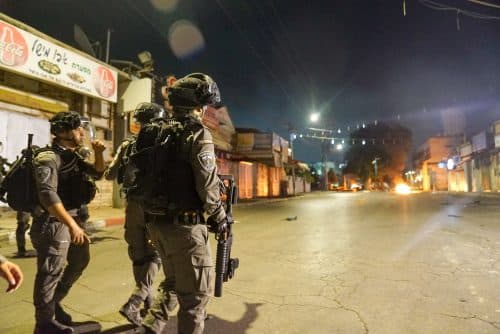

In order for Israel to maintain Jewish governance, we need Jewish settlement. It is evident that the military and police cannot maintain law and order in areas with sparsely organized Jewish settlement. We can see this when comparing the Bedouin townships that are studded along both sides of the two major transportation arteries in the Negev: The Be’er Sheva-Arad rout, and the Be’er-Sheva-Dimona rout (which is rife with stoning attacks on passing cars) – and their counterparts in the Sachnin area, where the Jewish settlement bloc of Gush Misgave is. The presence of Jewish citizens in that area creates a markedly different environment.

In other words, what we have here is a dynamic of a national struggle over the land. The only means with which to prevent a hostile takeover of the area is Jewish settlement in the frontier areas. The bourgeois policy, which turns a blind eye to the reality of struggle, reflected in National Outline Plan 35, is forsaking the territory to our adversaries.

Not Only to Provide Governance: A Deep-Rooted Connection to The Land and Our Identities

In addition to strategic considerations of the struggle for governance and territory, there is also a significant ideological reason to return to non-urban settlement. According to Ben-Gurion’s vision, agricultural settlement strengthens our cultural heritage and connection to our homeland. Trekking the trails of our country is nice, but hardly sufficient.

Taking a look at European countries, even the most developed among them, shows that non-urban settlement is a very common practice there. For example, about two-thirds of Germany’s citizens do not live in urban areas. Even those who work in industry or high-tech in urban centers own rural property, and when they retire, they return to work their land. In Italy and Spain, for example, the olive harvest is a family holiday that is part of the local culture. In order not to harm the cultural experience of working the land, they even avoid using technologies that would make short work of the harvest and spare the family the need to partake in the labor.

Sounds economically unsound? True. In order to create a deep bond with the land, we will have to bear economic prices. Taking and example of my Druze neighbors in the Golan – when they plant orchids, they are well aware that the harvest will not necessarily return their investment – sometimes not even within 100 years. They are motivated not by economic considerations but by the desire to cultivate their living habitat in which their cultural autonomy and heritage will flourish.

The fundamental difference between a person who is connected to his land and one who is not is the connection between his identity and the place where he lives. In Israel this connection is critical, as we live in a perpetual state of conflict over our living territory and it is imperative that we cultivate our identity’s connection to it. Only a people connected to its land is able to hold on to it over time, fight for it and prevail the hardship it presents.

Curbing Settlement: The Three Processes Underlying National Outline Plan 35

As mentioned earlier, National Outline Plan 35 carved the country into four major metropolis zones, around which it designated construction. But at the base of the plan were additional elements that changed the situation de facto.

The first element was the growth cap on rural Jewish settlements. No such cap was set for any Arab settlement.

Take the following illustration: near Rosh Pina there are two neighboring settlements – Tuba-Zangaria and Kfar Hanasi. In 1955, each of these communities had 200 households. National Outline Plan 35 set a quota of 400 households for Kfar Hanasi and 10,000 for Tuba-Zangaria. It is important to understand: the disparity is not only between the 400 and 10,000 households, but in Kfar Hanasi 400 is the maximum number, while in Tuba-Zangaria this is only the beginning of the process, with no limitation on expansion. Thus, a policy of restrictions on Jewish townships and settlement began, whereas Arab towns received broad-range development plans.

This is a subversive event, as it sells people an supposedly irresistible idea, not unlike the idea of preserving open spaces. But developments on the ground led to a completely different outcome, which could have been foreseen from the outset, and if the public had understood this in advance, it would not have acquiesced. The experts who led this move were post-Zionist academics from the disciplines of geography and law, and the policy drew from the opinion they put forth: it would not be possible to establish new Jewish settlements in all areas of the country.

The second component is the admissions committees. According to law, admissions committees can only be held in communities with no more than 400 families. In communities where no such limiting quotas apply, once they reach 400 families, their land cannot be marketed by the usual means, which includes an admissions committee that selects the buyers that are most suitable to the community’s character. To expand the settlement, an Israel Land Administration tender must be held, wherein the land is sold to the highest bidder. Such a tender hikes the price of the land, and it is no longer within reach for the local residents. Ostensibly, there is no discrimination here. But when the Civil Administration issues a tender for land in Arab localities, it contains an explicit clause stating that the land is designated for the residents of the community alone. Thus, a situation is created wherein a young Israeli couple must compete over land, while Arab couples have no such need. They are protected.

The third element in the desolation of the Jewish settlement enterprise in Israel is the government’s conflict of interest. After all, housing purchase tax is paid as a percentage proportionate to the cost of the property. The more expensive an apartment or house – the more money pours into the state coffers. It is important to remember that the state is also in effect the seller, and it naturally prefers to sell land in the higher-costing center of the country. In addition, it is economically favorable for the government to designate the same land for high-rise apartment towers, for which developers pay higher sums. Thus, for every new apartment bought, the state pockets a two-fold profit: once when the developer purchases the land, and a second time when the buyer purchases the finished apartment. In other words, if we look at it from an exclusively economic perspective, the government has a clear interest in us living in apartments, especially in the center of the country.

The State of Israel must put aside its economic interests in this matter, and strive to maintain its full sovereignty over the territories of the Negev and the Galilee. Rezoning plans for the country’s geographic periphery will afford the State fuller control over these areas, connect us to our agricultural heritage and ground our national identity. Not to mention bring down housing prices for young Jewish families. Or in other words: put the engine of the Zionist enterprise back on track.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the movement